I wanted to catch Bluetooth devices like Pokemon. Turns out, the radio spectrum had other plans.

This is the story of a 6-day project built entirely by prompting Claude Code. No manual coding. Just conversation, debugging, and a lot of log files. 11,000 lines of C, 241 build attempts, an idle game running on an ESP32-S3, and some interesting discoveries about what LLMs can (and can’t) do with embedded systems.

The Idea

It started with a prompt:

“I want to build a handheld device that scans for Bluetooth devices and collects them like Pokemon. It should run on an ESP32 with a small touchscreen display.”

The assumption: every BLE device broadcasts stable features (manufacturer ID, service UUIDs, device name) that could be hashed into a fingerprint. I figured you’d just scan, hash what you see, done.

In retrospect, if you’re a device manufacturer spending engineering effort to rotate MAC addresses for privacy, you’re probably not going to broadcast a stable identifier that defeats the whole point. But I didn’t know that yet.

One of the first questions I asked:

“Are you required to pair to be able to probe all of the characteristics for the BLE connection?”

Turns out there are three levels of data access: passive scanning, active connection, and pairing. Each reveals more, but also requires more cooperation from the target device. I went with passive-only. No connections, no pairing. The device you’re scanning doesn’t even know you exist.

Surely it wouldn’t be that easy.

claude researched what was needed: Docker image, ESP-IDF, LVGL, the whole toolchain. I had it break the plan into tasks in qask and start building. (More on this approach in Long Running, Complex Development with Agents.)

The initial scaffolding ran for 117 minutes unsupervised: 23 subagents spinning up, reading specs, generating code, reviewing each other’s work. I came back to a project structure, build system, and code that compiled. Whether it actually worked on hardware was another question.

With a build in hand and the hope that it would actually work on device, the plan was to extract everything a BLE device advertises and hash it into a fingerprint:

// components/fingerprint/include/fingerprint.h:18-44typedef struct { uint8_t oui[3]; // First 3 bytes of MAC bool is_random_addr; // Whether MAC appears randomized char device_name[32]; // Complete or shortened local name uint16_t appearance; // GAP appearance value int8_t tx_power; // Transmit power level uint16_t manufacturer_id; // Company identifier uint8_t manufacturer_data[64]; uint16_t service_uuids_16[16]; uint8_t service_uuids_128[4][16]; uint16_t adv_interval_ms; // Advertising interval int8_t rssi_avg; // Average RSSI} fingerprint_features_t;OUI, device name, manufacturer data, service UUIDs. Surely something in there would be stable across MAC rotations.

The fingerprint computation ended up in fingerprint.c:495-500:

// components/fingerprint/fingerprint.c:495-500// Compute SHA-256 and truncate to 64 bitsuint8_t sha256[32];mbedtls_sha256(buffer, pos, sha256, 0);

// Take first 8 bytes as fingerprintmemcpy(hash_out, sha256, 8);The Reality Check

Fighting the Hardware

Day two was where hopes met reality and turned into a debugging marathon. Most of my prompts were some variation of “it still doesn’t work.”

The display came up mirrored. claude fixed that. The colors were wrong: purple where there should be white. claude fixed that. Touch events weren’t registering correctly. The x-coordinate was stuck at 96 regardless of where I tapped. Systematically I’d tell claude what was broken, it would try to fix it, and the churn continued until the issues were resolved. However, it was whackamole: fix one issue, another pops up.

Note (ESP-IDF)

I’ve never actually done anything with an ESP32 board, nor anything with ESP-IDF; the blind leading the blind.

While I had something showing signs of life, it was still far from a working embedded application. The UI wasn’t responding to touch or displaying anything other than the first frame of the startup screen. I didn’t have enough context to really steer claude. And claude didn’t have enough inherent knowledge to just do the right thing.

After a while, I had to step back:

“Perhaps it’s time to take a step back. It feels like just a lot of guess work instead of critically thinking about the problem. Let’s take a look at vendor examples: https://files.waveshare.com/wiki/ESP32-S3-Touch-LCD-2.8/ESP32-S3-Touch-LCD-2.8-Demo.zip and see how they are using the touchscreen and BLE connection.”

The breakthrough came from downloading the Waveshare vendor example, pointing claude at it to review the examples, and coming up with an understanding of how to properly set up LVGL.

At this point I decided to focus on just bringing up LVGL and disabled the BLE part. In the examples, claude found a critical piece. LVGL requires a periodic timer calling lv_tick_inc() to advance its internal clock. Without it, the framework thinks no time has passed and never redraws after the first frame.

// components/display/display.c:110-113static void lvgl_tick_cb(void *arg){ lv_tick_inc(LVGL_TICK_PERIOD_MS);}One timer callback. Hours of debugging. To be fair, most of these hours were filled with other activities; actual time spent with claude was quite a bit less.

Then came the BLE watchdog crashes. The device would boot, catch a few BLE devices, and hard crash:

Guru Meditation Error: Core 1 panic'ed (LoadProhibited)EXCVADDR: 0xecf9ecfdThe address pattern 0xecf9ecfd looked like corrupted/freed memory. To decode the crash, I told claude to use addr2line inside Docker (I didn’t want ESP build cruft all over my system):

docker compose run --rm idf xtensa-esp32s3-elf-addr2line \ -e /project/build/ble_pokemon.elf -fipC \ 0x4206ce75 0x4206d1fe 0x4206d24f 0x42003146 0x40382423The backtrace pointed to task watchdog code:

find_entry_from_task_handle_and_check_all_reset at task_wdt.c:153esp_task_wdt_reset at task_wdt.c:712idle_hook_cb at task_wdt.c:468Close I guess, but didn’t seem like anything really actionable.

The crash was in the watchdog code, but caused by BLE scanning on one core starving tasks on the other. The ESP32-S3 has two cores, and the pattern revealed the real issue: BLE controller runs on Core 0 (PRO_CPU), while LVGL and application logic need to run on Core 1 (APP_CPU).

claude figured this out by analyzing crash dumps and cross-referencing with ESP-IDF documentation. I just watched the machines work and was along for the ride.

printf debugging; with pixels

The device wasn’t crashing. The display wasn’t mirrored. Time to give claude a way to see what’s actually going on.

Note

claude is multi-modal, so “seeing” images/screenshots is a fairly effective way to work with it. This is a common pattern for frontend development. The only challenge is I had no idea how to accomplish this with the ESP32.

Where there’s a will, there’s a prompt:

“Is there a way to dump the display buffer over the wire so you can generate a ‘screenshot’”

This led to screenshot.c: a serial-based screenshot capture system. The device renders to a buffer, hex-dumps it over the serial port, and a Python script on the host reconstructs the image.

One wrinkle: LVGL uses BGR565 internally, so the decoder has to swap the channels:

# tools/decode_screenshot.py:40-46def rgb565_to_rgb888(rgb565: int) -> tuple: """Convert RGB565 to RGB888 (with R/B swap for LVGL BGR565 format).""" b = ((rgb565 >> 11) & 0x1F) << 3 g = ((rgb565 >> 5) & 0x3F) << 2 r = (rgb565 & 0x1F) << 3 return (r, g, b)With this implemented, fixing up the UI became a lot easier: screenshot, berate the machine, analyze, fix, repeat.

The Data Doesn’t Lie

With the hardware working and a basic “Pokedex” UI in place, it was time to find out how well the fingerprinting would actually work. I was seeing a bunch of devices, but none had clear names and the amount of “devices” showing up was way more than I expected.

“Add a log file for all of the ble data we collect for the fingerprints. This allows us to collect a lot of data while in the wild. Then I will give you the log file to do in-depth analysis.”

Away claude went. It built a logging system, I flashed it to the device, let it run, and ended up with 51,000 entries in a CSV file. That’s a lot of data and I had no desire to sort through it myself.

Time for another prompt:

“Launch 5 “expert” subagents in parallel to make sense of the ble_log.csv: device diversity, Apple protocols, any noticeable patterns, vendors, fingerprint quality, and RSSI analysis.”

What resulted was much disappointment and a bit of confusion.

The Net is Vast and Infinite

First discovery: the radio spectrum is noisy. I was seeing devices I knew weren’t mine, and a lot of Apple traffic.

claude’s analysis matched auth tags to known devices and found a clear RSSI separation:

| Device | RSSI | Owner |

|---|---|---|

| Mac #1 (auth 1A6D70) | -52.8 dBm | Likely mine - closest |

| iPhone (3 rotating tags) | -66 dBm | Likely mine |

| FELLOW518F (smart kettle) | -87 dBm | Neighbor’s |

| Bespoke Jet Bot (robot vac) | -90 dBm | Neighbor’s |

We were picking up neighbor’s robot vacuums, smart kettles, health monitors, adjustable beds. Everything with a Bluetooth radio within 20 meters.

The RSSI Histogram

51k samples, visualized:

-90 dBm | ████████████████████████████████████████ 12,653 (24.8%) ← Peak -85 dBm | ████████████████████ 6,319 (12.4%) -80 dBm | ████████████████ 5,142 (10.1%) -70 dBm | ███████████ 3,435 (6.7%) -60 dBm | ███████████ 3,779 (7.4%) -50 dBm | ██ 349 (0.7%)The -90 dBm peak is “neighborhood background radiation”: signals from apartments 15-25 meters away through multiple walls.

| RSSI | Distance | What’s there |

|---|---|---|

| > -60 dBm | < 3m | Your devices (9.6%) |

| -60 to -80 | 3-15m | Same apartment (30.9%) |

| < -80 dBm | 15m+ | Neighbors (59.5%) |

Nearly 60% of all BLE traffic was noise from neighbors’ devices.

The Hard Truths

Remember that optimistic struct? Here’s what actually happened to each field (in hindsight, it would be a massive privacy issue if you could easily identify and track devices with a $20 gadget):

device_name: Empty. iPhones don’t advertise names. They’re not looking for new connections; they’re already paired with their accessories. Privacy by design.

oui and manufacturer_data: Rotating. One auth tag appeared with 40+ different MAC addresses, sometimes rotating sub-second. The OUI went with it.

service_uuids: Mostly generic. The same handful of UUIDs appeared on hundreds of different devices.

Out of 202 unique device fingerprints, only 8 had names. That’s 1.7%. The whole “catch named creatures” concept couldn’t work.

Apple’s Auth Tag Trick

One finding was genuinely interesting. Bytes 5-7 of Apple Continuity messages contain an “auth tag” that persists across MAC rotations. We found the same auth tag (0x65BA38) appearing with 40+ different MAC addresses: proof it’s the same physical device.

// components/fingerprint/fingerprint.c:402-417case 0x10: // Nearby Info // Structure: type(1) + len(1) + status_action(1) + data_flags(1) + // ios_version(1) + auth_tag(3) if (mfr_len >= 8) { // Authentication tag (3 bytes) - persists across MAC changes! out[pos++] = mfr_data[5]; out[pos++] = mfr_data[6]; out[pos++] = mfr_data[7]; } break;But even this couldn’t save the Pokedex concept. Auth tags 65BA38, 65BA78, and 65BA28 had similar prefixes and RSSI. Were they one iPhone rotating tags, or three different neighbor iPhones? With 66% of traffic being Apple devices, it was impossible to tell.

The Pivot

No Pokedex. But we had 51,000 reasons to try something else:

“Now that we have a lot more data to work with in the ble_log.csv, we can re-think the gameification side of this. Given that we can’t easily get the Device Name, is there something else that could make this a bit more interesting? Maybe more of a tamagotchi? Or some idle incremental game based on beacons for leveling?”

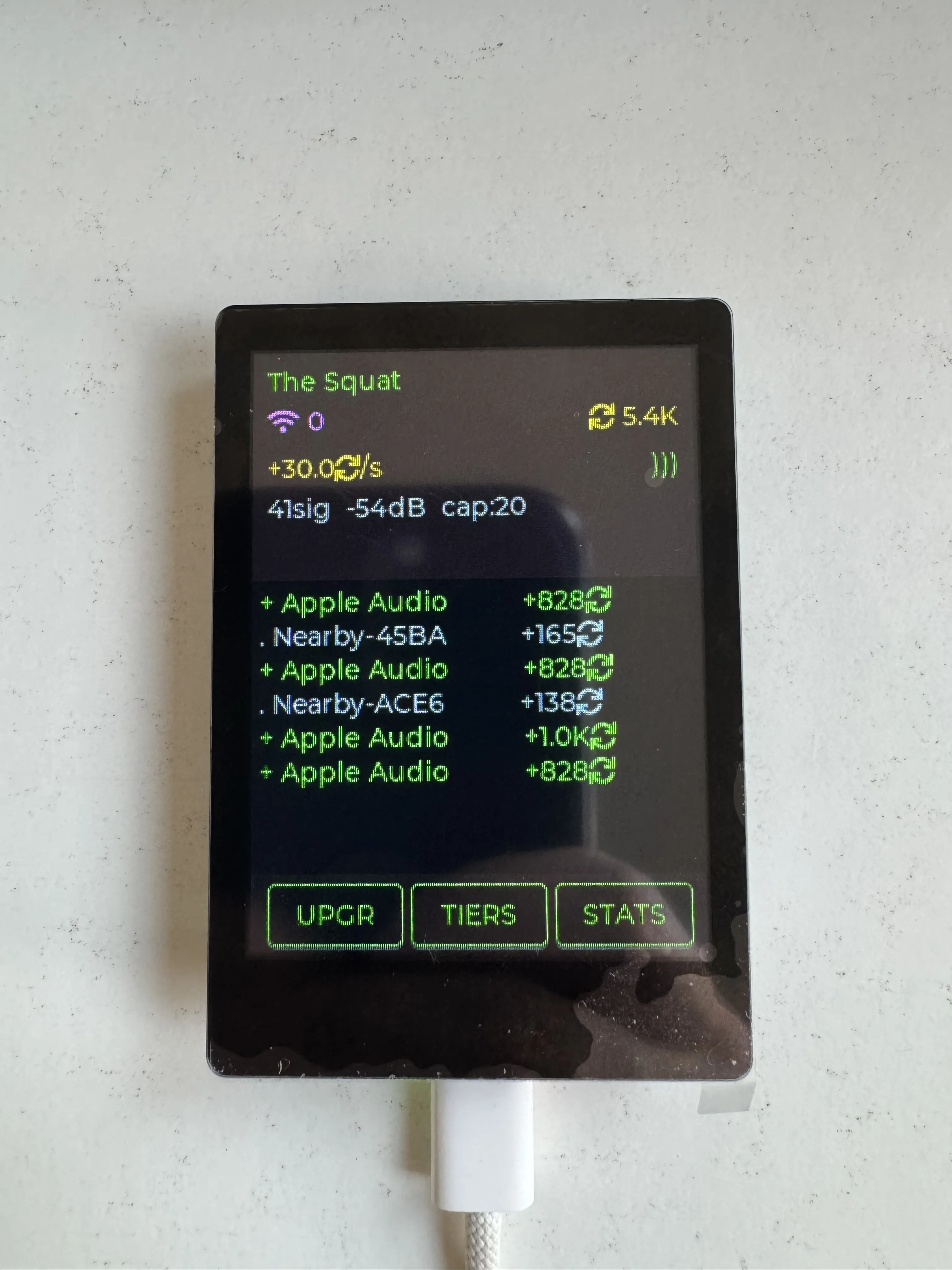

claude proposed several ideas. I was already leaning towards an idle game, so “Idle Signal Farmer” seemed like an acceptable second place.

Note

Idle games are simple (numbers go up; numbers get big), and we had a real-world source of numbers. If you’ve ever lost an afternoon to Cookie Clicker or Idle Slayer, you know the dopamine loop. Why not hook it to real radio traffic?

But the idea was half-baked and needed a whole set of progression/upgrade/gameplay loops:

“Idle Signal Farmer seems a bit more interesting. Flush that idea out more.”

Fortunately, those 51k data points (with timestamps) became the foundation for game balance:

The starting range problem. Remember that RSSI histogram? Only 9.6% of traffic was within 3 meters. If you could see everything from the start, there’s no progression. So the game begins with a -50 dBm threshold: you can only harvest signals from devices within arm’s reach. That’s maybe your phone and your laptop.

Antenna upgrades as progression. Each upgrade lowers the threshold by 1 dB, gradually unlocking the “neighborhood background radiation.” By the time you hit -90 dBm, that 60% of neighbor traffic becomes harvestable. More signals means more currency, even if each weak signal pays less.

Rarity from the data. The 202 unique fingerprints told us what’s common and what’s rare. Apple devices (66% of traffic) became “common” signals. Devices with actual names (1.7%) became rare finds worth bonus currency. The neighbor’s robot vacuum with its weird dual-packet format? That’s a “ghost”: genuinely unique, genuinely valuable.

The dataset that killed the Pokedex became the balancing spreadsheet for Idle Signal Farmer.

Reflection

So what did this project actually demonstrate?

The domain wasn’t “too hard” for an AI. ESP-IDF, LVGL, BLE protocols, FreeRTOS threading: claude could be coaxed through all of it. The debugging session found the lv_tick_inc() issue after being given the Waveshare examples. The protocol analysis parsed 51,000 log entries and drew useful conclusions.

It’s by no means perfect. Some UI decisions needed multiple iterations. The token cost of embedded C adds up. The UI is a bit rough. But for a few days of effort in an embedded framework I’d never touched, on hardware I’d never flashed, that’s quite a bit more than I expected.

The game itself is secondary.

What was interesting: watching an AI debug a watchdog crash, seeing it analyze auth tag patterns in BLE packets, having it teach me enough about BLE privacy that the pivot became obvious.

A few days from prompt to holding something in your hands. Whether that’s useful or just novel, I’m still figuring out.

(For the full breakdown: 6 days, 241 builds, 794 file edits, 46 context continuations. See Idle Signal Farmer: The Numbers.)